Julian Walker - art and heritage

Work engaging with museums, historical sites, and heritage objects, 1990 to 2024

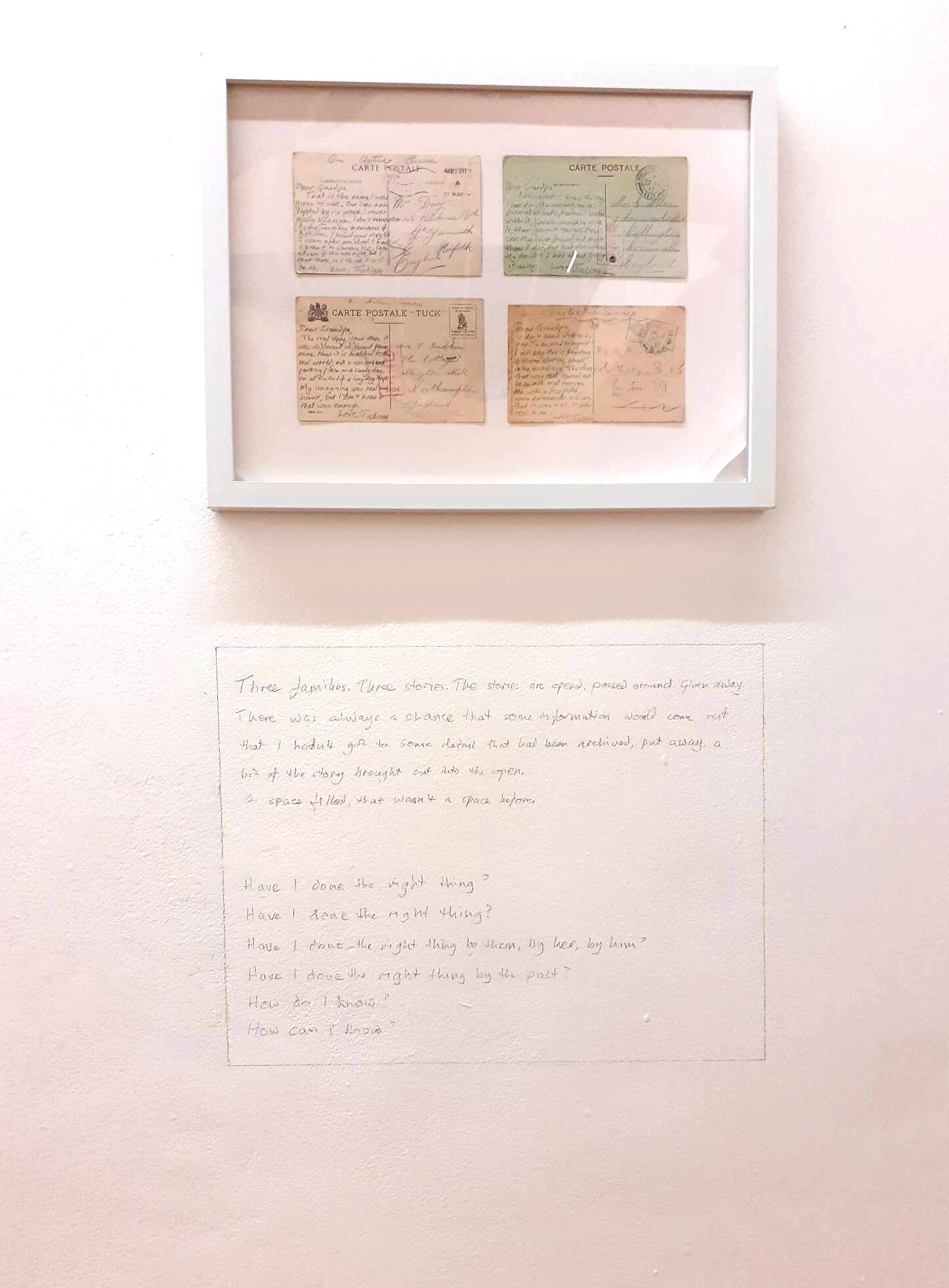

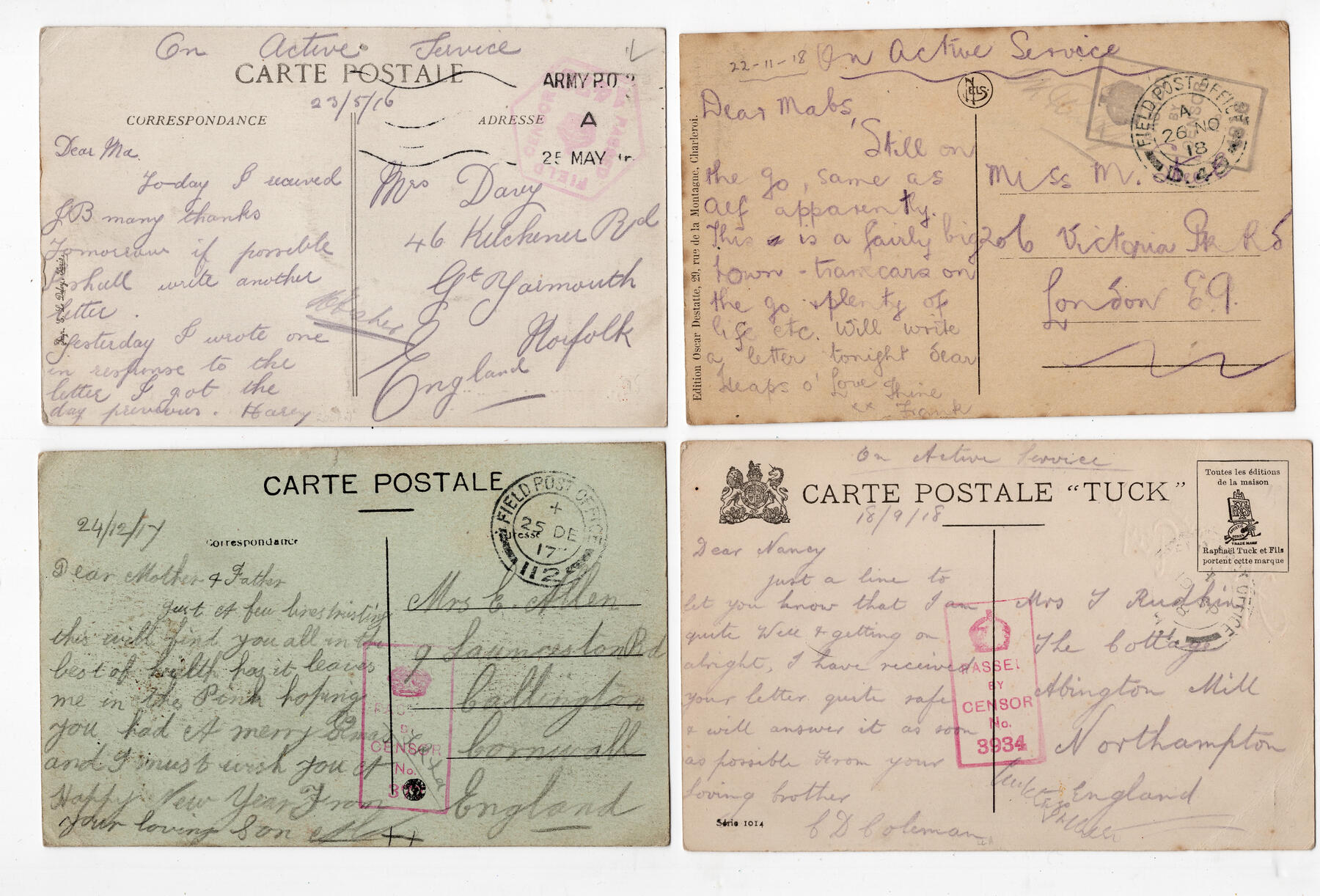

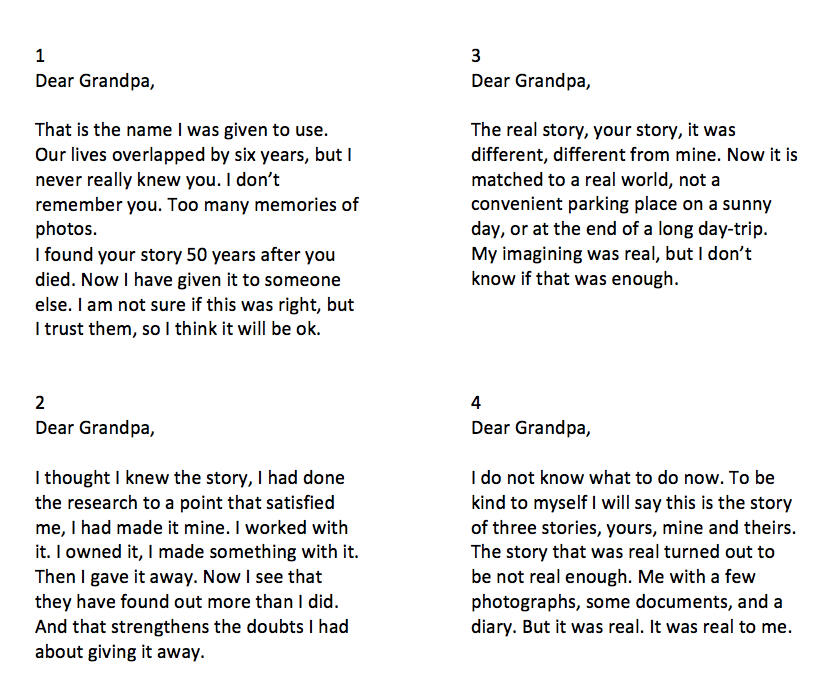

Postcards to my grandfather (2023)

Four postcards written home by soldiers during the First World War, text erased and rewritten.The deliberate destruction of historical material in Four Postcards to my Grandfather suppresses the archival drive in favour of direct communication with the past. Archives destroy memory. Here the sharing of the archive within the context of an unremembered relationship raises issues of privacy, failure and ownership.One of the works made for Borderlines, Front Lines (ISELP, Brussels, 2023) was part of a collaborative work in which family archive material and memory was shared with Philippe Black and Sam Vanoverschelde. It comprises four altered postcards. The postcards were written and sent to addresses in England between 1916 and 1918 by British soldiers on active service in France or Flanders during the First World War. On each one the correspondence section has been almost completely erased, and written over with my own text, four messages to my grandfather, who also served in these areas between 1916 and 1918.As the destruction of historical material sometimes excites comment and protest it is useful to discuss certain points, and to consider some implications.The destruction of cultural material as an act of creative art is not new. Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased De Kooning Drawing was made before I was born. The artwork is both the act of erasure and the erased drawing as evidence of the act. For hundreds of years previously cultural artefacts have been made by consciously recycling, reworking, overpainting, and incorporating other older cultural artefacts.I have been using this process, partial erasing of historical cultural material, with the addition of my own work, for over 20 years, using a range of media.Each postcard was selected for not being special; in each case part of its value lies in its lack of differentiating features, its similarity to so many hundreds of thousands of other postcards, referencing a huge commonality of experience. Each one is also an individual experience.People have in the past asked with regard to my working in this way, how I would feel about my own work being erased. This is one reason why I have written the text in pencil. It is both a reference to the original medium used, an acknowledgement that the point is valid, and laying the work open to future intervention.Every one of these postcards has lost contact with the family concerned. In each case the card would have been easily traceable by a researcher, and was sold via a well-known internet marketplace. Of the four soldiers who sent the cards, two may have been killed in action after the cards were sent, and two survived the war.For archival purposes a record both of the original text, and of my erasing it, was kept. To be erased at the end of the exhibition.And, since this work stems from the First World War, a phrase from that conflict is relevant. Amongst the heavy-industrialisation of death cynicism flourished, truth pared of all presentation; in order to get the soldiers out of the trench to face a heightened risk of death one officer was heard to encourage them with the words ‘Come on, do you want to live for ever?’

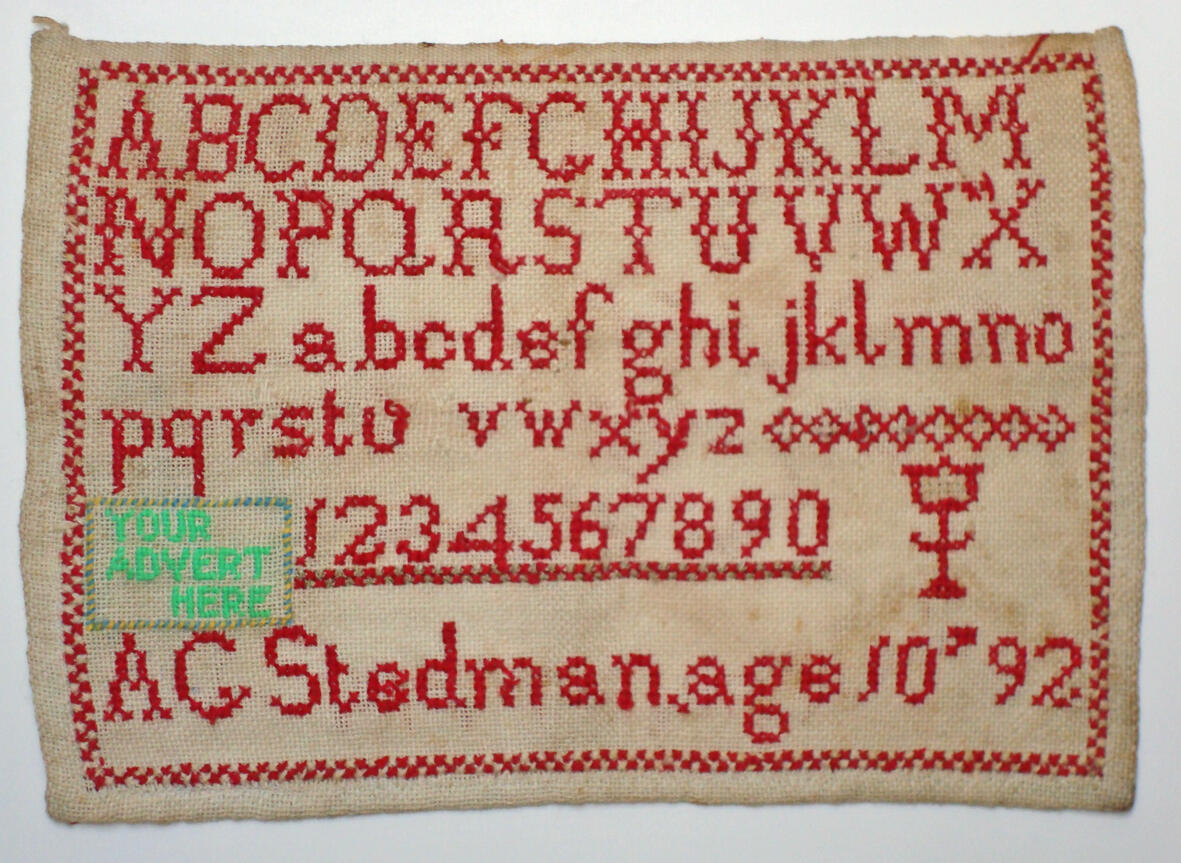

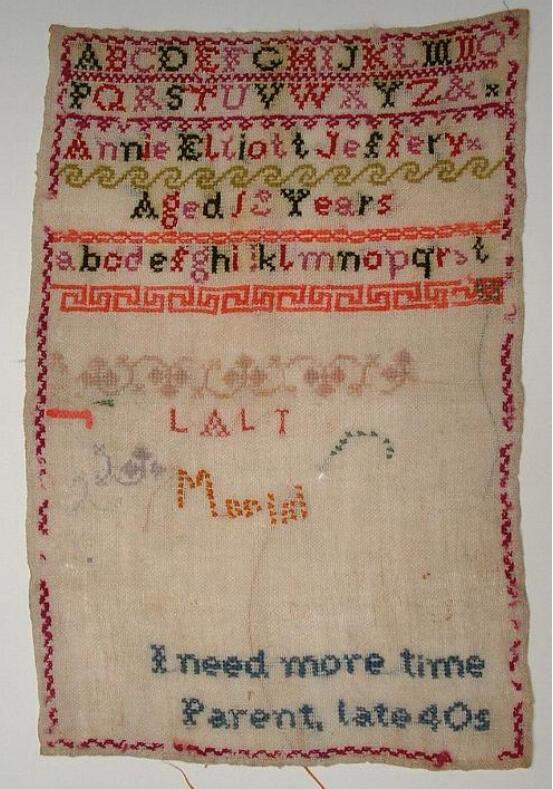

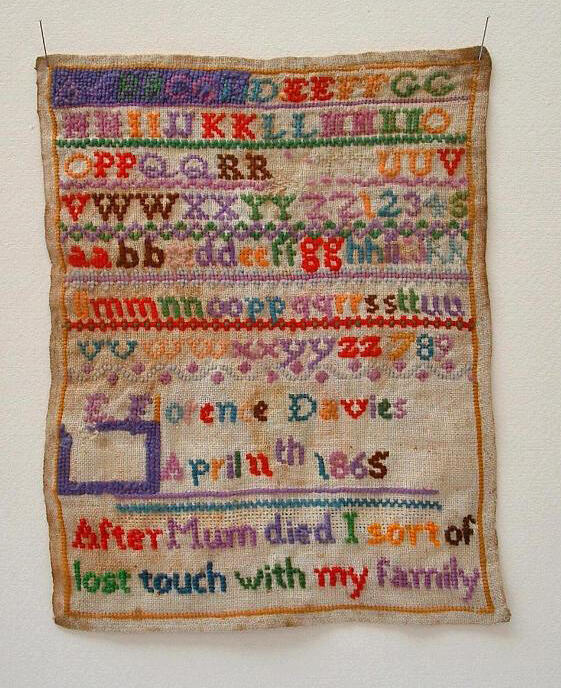

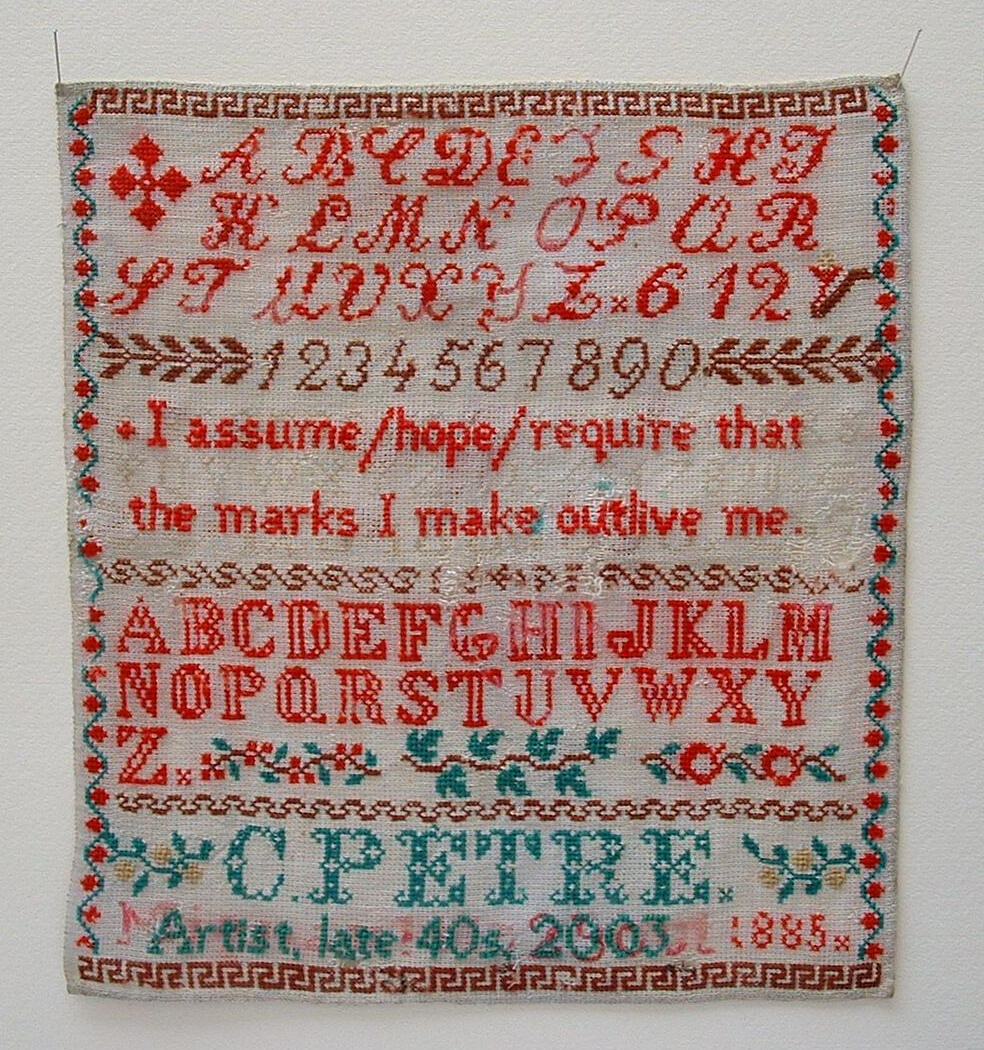

Interventionist Embroidery (from 2003)

"Sample" The Embroiderers' Guild

August 2003 -May 2004

Williamson Art Gallery, Birkenhead

Dutch Textile Museum, Tilburg, Netherlands

Hall Place, Bexley

2012 - Art in Romney Marsh

2013 - Subversive Design, Brighton MuseumThe work for this touring exhibition comprised a number of nineteenth century child-made samplers which were altered by unpicking parts of the original text and images and replacing them with my own. The texts of sentimental received truths were replaced with new texts reflecting adult and parental fears and doubts at the beginning of the twenty-first century.Responses to the work, alongside its potential for exploring concepts such as violation, dialogue across time, the continuous process of art as a conversation, led me to continue working in the medium. Further exhibitions of this kind of work included 'Home' at Contemporary Applied Art 2015, Subversive Design' at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery 2013, 'Art in Romney Marsh' 2012, 'Unravelling Nymans' 2012.Several issues are raised by this body of work, not the least of which is the physical intervention by a male artist in work made by young women. There are also questions of whether the work itself invites further intervention, how it changes folk art into fine art, and whether destruction and creative activity can be reconciled.

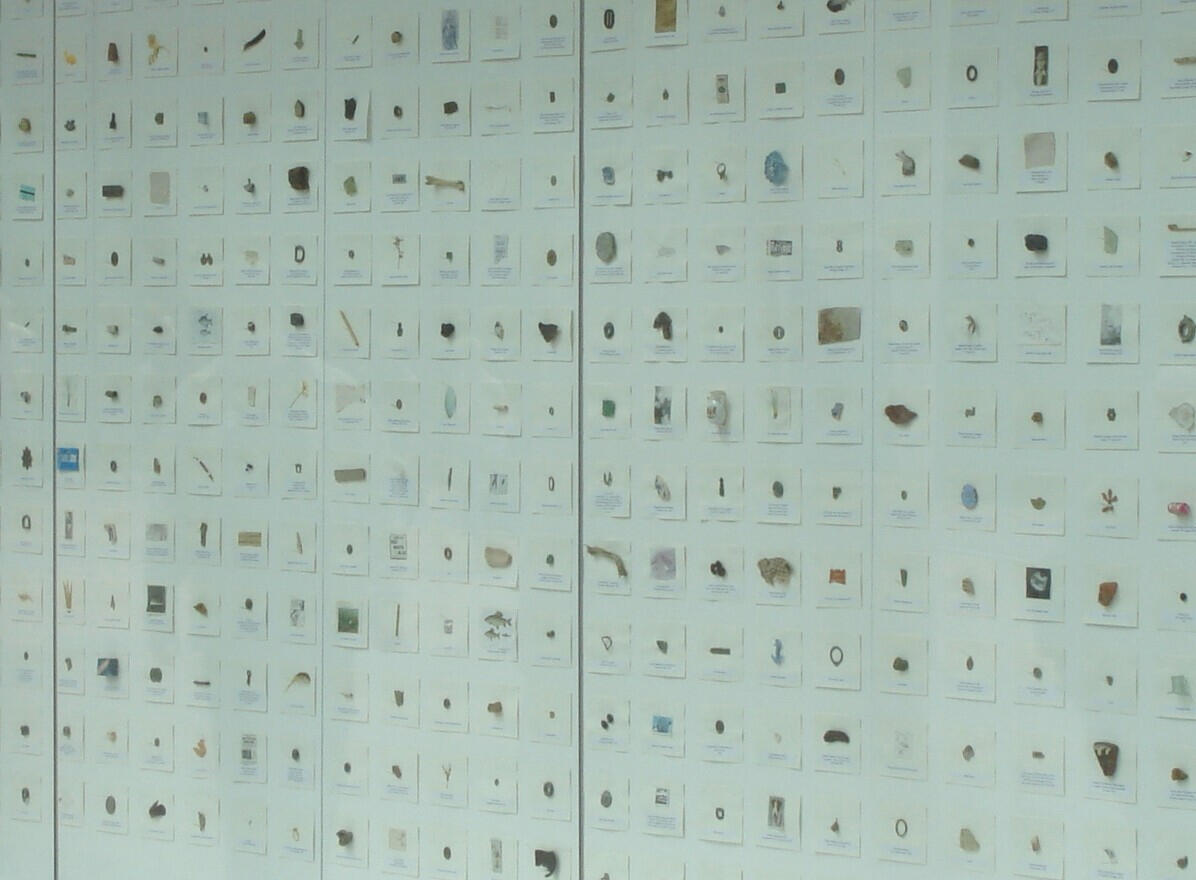

Births, Chimneys and Lightermen – Collecting Greenwich Peninsula (2008)

The Greenwich Peninsula is an area that has undergone repeated change over the past 500 years, and yet remains one of the least known parts of London. Though many Londoners know well the Blackwall Tunnel Approach Road, and hundreds of thousands of visitors go between North Greenwich Station and The O2, few walk the area between the south and north of the peninsula, with its mixture of luxury apartments, Victorian terraces, thriving chemical factories, retail parks, shadows of London’s industrial past, and unexpected open spaces.Like so many better known parts, the peninsula has acted as a stage on which the roles of London have been performed. The drama can be read in a number of ways: as land use – marshy wilderness, agricultural, industrial, cheap housing, dock services; as the products of and for the city at the centre of empire - soap, cement, sugar, chemicals, linoleum, ammunition, cabling, gas, boats, tar, paint, benzene; in the occupations of its inhabitants – market-gardeners, scavengers, industrialists, laundresses, shopkeepers, lightermen, munitions workers; and in how their lives were recorded – in census, parish and workhouse records, in maps of tithes, bomb damage or relative social status, in newspapers and the writings of Mayhew, Dickens, Gissing and others.Looking at the history and the present of the place, famously described by Iain Sinclair as “where the nightstuff was handled”, there is no sense of a “coherent proper state” or any form in which the place has achieved its most appropriate condition. How then do we invent an identity for the area?Births, Chimneys and Lightermen – Collecting Greenwich Peninsula has been commissioned as an installation for the Story Wall between North Greenwich Station and The O2, which explores how we negotiate a sense of place. Using research findings which include aspects of demographics, geology, archaeology and natural history, the work is a vast grid collection of artefacts, objects, printed and drawn fragments and information, in which connections between object and text may be authentic, viable, fictional, imagined or arbitrary. The work invites viewers to create their own stories, which allow for continuous reinvention.In Doreen Massey’s words, “the throwntogetherness of place demands negotiation ... places as presented here in a sense necessitate invention; they pose a challenge. They implicate us ... in the lives of human others, and in our relations with nonhumans they ask how we shall respond to our temporary meeting-up with these particular rocks and stones and trees. They require that, in one way or another, we confront the challenge of the negotiation of multiplicity.”*; the work acts as a catalyst for that negotiation.This work continued collection-based installations shown over the previous 12 years in the UK and abroad, many of which have involved local residents.The art installation was commissioned by Art in the Public Realm Greenwich Peninsula, a consortium comprising: Arts Council England, Meridian Delta Ltd (Lend Lease and Quintain), English Partnerships, Greenwich Council and Greenwich Millennium Village Limited, working in collaboration with O2 / AEG* Doreen Massey For Space Sage 2006The work was on display from early February till late September 2008

Gone Away (2010)

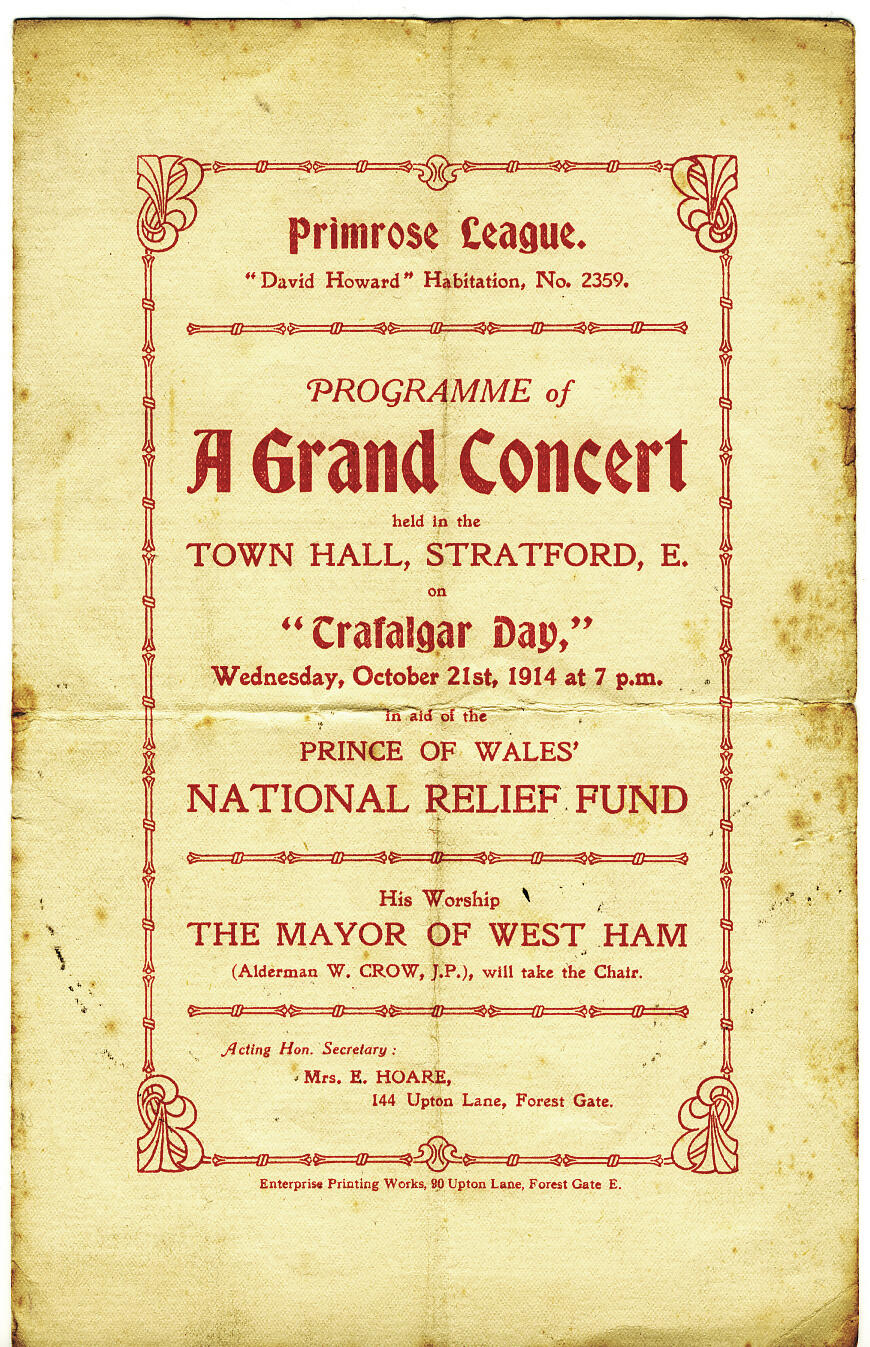

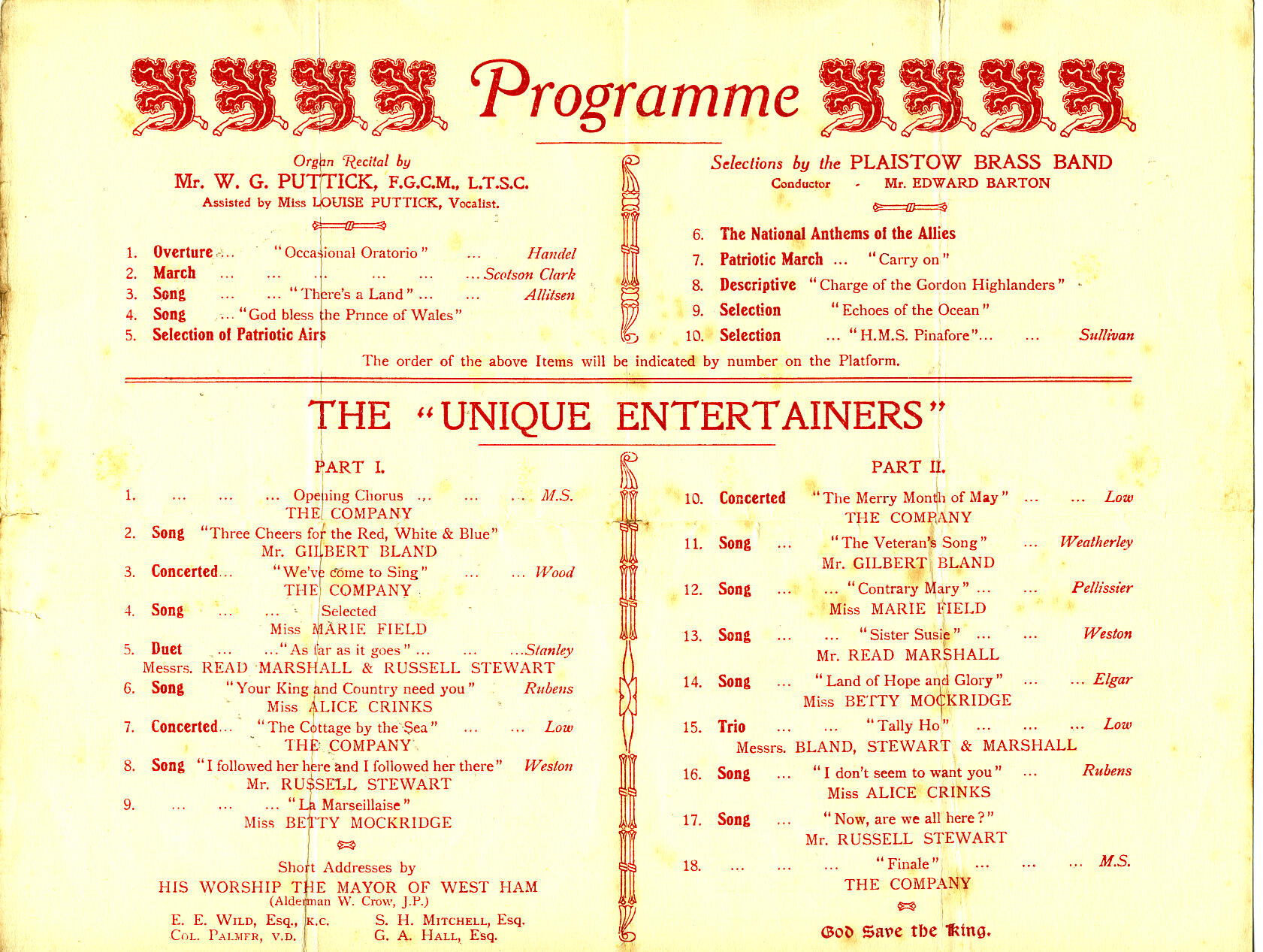

At the start of the First World War German armies invaded Belgium, causing a massive movement of refugees, about a quarter of a million of them being given refuge in Britain. From November 1914 to 1918 up to 67 refugees, mostly the families of postal workers, were given shelter in Valentines Mansion, Ilford. At first they were welcomed enthusiastically, and for many people this was an opportunity to patriotically support a country which came to be known as 'plucky little Belgium', even though some were aware of the institutionalised violence which had characterised the Belgian colonial exploitation of the Congo.Fundraising was carried out diligently over 1914 and 1915; concerts, whist-drives, social evenings, collections and flag-days all brought in food, clothing and money for the refugees. At one concert, in October 1914, in Stratford Town Hall, my grandfather, Fred Walker, under his stage-name of Russell Stewart, sang four comic songs.By late 1915 the funding had become institutionalised, and some were questioning the costs of fuel and support, and whether the refugees were doing enough to support themselves. By 1916 discrepancies over Belgian and British conscription, and the fear that Belgians were 'taking British jobs' were making people view the refugees less favourably, though by this time too the British government was secretly recruiting Belgian industrial workers in Holland to come and train British munitions workers. Thus in a sense Belgians were working to make the shells which were destroying their own land. While using Belgian support the British government was careful to keep track of the Belgian refugees so that they could be repatriated - 50,000 history cards are still kept at the National Archives, and have provided some of the names of the Valentines Belgians.By late 1917 most of the Belgians at Valentines had moved on, to find accommodation elsewhere, and the house was being turned into a maternity hospital.But following the German offensive in early 1918 more hospital space was required for British soldiers and there were plans to turn Valentines Mansion into a convalescent home. Views were expressed however, that this might be interpreted as 'throwing the Belgians out.'In 1918 my grandfather was stationed in a trench 100 metres from the Belgian border. His diary for Weds 9th Oct reads 'Gassed'; for Sun 13th Oct 'Began to see a little'; for Mon 11th Nov 'Armistice signed with Germany'.In 1920 the War Refugees Committee for Ilford petitioned the Council for permission to erect a brass plate in the Mansion stating that Belgian refugees had been housed there.The familiar stories of welcome, charity fatigue, generosity, bureaucratic control, and self-congratulation underlie this largely forgotten story of refugee migration, in an area whose identity is formed of migrating people. In workshops with clients of the Refugee and Migrant Forum for East London, local research enthusiasts, and staff and volunteers at Valentines Mansion, we are working through the story from different angles, and producing artwork which uses such elements as First World War postcards, soil from Belgian battlefields, fragments of wallpaper and rescued laths from the walls of Valentines Mansion, Congolese postage stamps, a newspaper advertisement offering free haircuts to Belgian refugees (not Saturdays), songs from the 1914 Stratford concert, and texts from Government memoranda.A key work is a video in which I sing the four songs my grandfather sang in the 1914 concert. The songs are performed solo in a field near where he was wounded in 1918.

Encounters with objects (2006)

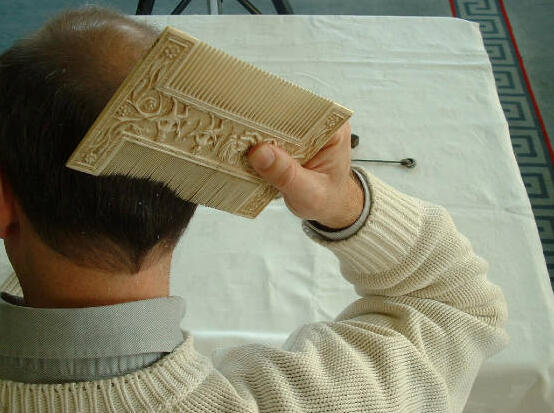

The Hunt Museum collection is a diverse group of objects, many of which were in use as domestic objects in the homes of the Hunt family. The idea that these objects were in a private house, treated as personal possessions, and in many cases used in accordance with their original intended usage, contrasts with their inevitable removal from usage as they become museum objects; yet they remain objects which visually convey the idea that they were made for physical use.The objects have changed their identities a number of times: made with specific intentions, which may be considered as their primary identity (1), mostly they then became stored, lost, hidden, used as decorative, treasure or grave goods (2), until their acquisition by the Hunt family (3), in many cases then reverting to their primary uses. On passing to the Hunt Museum they acquired a new identity as museum objects (4), for study or contemplation, referencing their roles at (2).Encounters with Objects comprises documented physical interaction with objects from the collection, in which the objects are treated as tools fulfilling the original purpose for which they were made. The work, a video of 8 short activities using selected objects, 8 photographic prints, and a number of text labels describing the experience of using the objects, tests the nature of the objects by re-using them in accordance with their original intended usages, including shaving with a Bronze Age razor, drinking from an 18th century cup, and combing hair with a mediaeval ivory comb.The work references a view of time as a helix along which points of repetition may be perceived creating lines of connection. It tests many ideas whose physical focus is the collection, including the nature of the projection of presence conveyed within the body of preserved objects, the nature and extent of the museum’s engagement with the objects, and how this relates to the Hunt family’s engagement with their collection. And for me, the whiole concept of intentionality - how do objects stop being 'museum objects' and become themselves as intended (which museums either avoid or fail to show)? One object that tests this clearly is a bronze age sword. How do you recreate the intention of a sword, what it really is?Well, I reckon that only a small part of the role of a sword is using it to kill someone. Its main role is to indicate to others and to the person holding or owning it that you/they have the power to kill someone. It is a power and status object. This is real when you are holding a sword. You look at yourself holding the sword. You test its weight and balance. You swish it. You know how it feels to have a sword in your hand. Believe me, it changes you.

Collection: Items Held (2005) - Art out of Place, Norwich

20 x 2.4 metresNorwich Castle, for most of its long history, was primarily a prison. Only towards the end of the nineteenth century did it become a museum, the cell-blocks and exercise yards which radiated from the central guard area becoming galleries to display art, historical artefacts, taxidermy specimens, rocks, fossils and examples of applied arts.The familiar opposition between what I know and what I see is central to my experience of this site, the "what I see" being the museum, and the "what I know" being the much longer history of the site as a prison. Is it possible to bring together simultaneously these two identities, to know together the two times of the one place ? What happens in the changing of the place from a site of misery to a site of treasuring: does the melancholy linger? Do the boredom, the fear, the repetitive tasks become museum objects? Was there inherent in the prison a sense of items extra-ordinary, different, and curious?This work comprised over 4000 objects in a grid on the wall of the Timothy Gurney Gallery at Norwich Castle Museum. Each item was labelled with the hand-written name of someone who at one time was held on the site as a prisoner. The items were in a sense all failures of the museum test: they were broken, torn, bent, corroded, dirty, burned; fragments or fragmented; the commonplace, the not very interesting, the cheap version; copies, forgeries, pastiches; covers, mounts, labels. Never the real thing, or if they were, then there only by a mistake of judgement.And the identities were those of people who spent time imprisoned here for crimes ranging from rape, murder and rebellion to the theft of a smock, a turkey or a loaf of bread, or simply for following the wrong faith. Some were executed, some were repeat offenders, and some were no doubt entirely innocent. Their crimes, like their names, were peculiar to them, but become repetitive, expected, almost as inevitable as the stuffed birds, the landscape watercolours, the fossils and the Roman coins. Some indeed stand out; the murderer, the polar bear, the hero’s hat, the transportee turned successful businessman, the leader of the rebellion, the prison Bible, the painting of the bridge. Mostly they pass before our eyes, a succession of objects, names, dates, statements, inviting occasional scrutiny; the object so like one I have at home, the name so like my own.Objects and identities are linked here by the fact that they were put in a safe place removed from circulation, through the well-intentioned offices of an authority working for the improvement of society.I suspect that the work is mostly about time, or times. An anagram of "items".Perhaps the most poignant aspect of the work came when it was being erased. Something I was told later. Two people who repaired the wall after the objects were removed - only the objects, not the names - came across two names they recognised as long-dead family members. I was told that they cleaned the wall of names, except for these two, who they left alone for a while, before also removing them from the record.

Mr & Mrs Walker have movedKettle's Yard (with Anne Eggebert) (1998)

In the summer of 1998 Anne Eggebert and Julian Walker were invited to propose a site-specific work for Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge. Kettle’s Yard is ‘a beautiful and unique house containing a distinctive collection of modern art. Kettle's Yard was founded by H.S. 'Jim' Ede as a place where visitors would 'find a home and a welcome, a refuge of peace and order...'[1] The house museum contains a closed collection of 20th century art, antiques, and found objects. It was developed by Jim Ede with the idea that ‘art [is] better approached in the intimate surroundings of a home’[2].The house at Kettle's Yard is the former home of Jim Ede and his wife, Helen, and contains a substantial collection of 20th century artworks displayed alongside furniture and other objects in the unique setting that Jim created. Jim Ede's idea was 'that art [is] better approached in the intimate surroundings of a home'. Kettle's Yard is designed as 'a refuge of peace and order', an act and site of spiritual contemplation. It is proposed as a model for English domestic settings/interior design which 'could be anywhere and for some reason it isn't'."We recognised that Kettle's Yard offers a cultural model for the perfect living space that we desire. However, we are aware that this environment which is proposed as something natural is a tightly constructed English aesthetic. We considered the ambivalence of the delight of being in the space alongside the oppressive care of negotiating our way amongst the objects"We decided that the best way to test Ede's idea of Kettle's Yard as a domestic living space and not a museum was to move in as a family. On the 16th June we invited guests to visit us and our 2 year old son in our new home.We installed CCTV cameras around the house, including its bedrooms, the cameras relaying images of our activities to a monitor facing the street. Members of the public were able to witness us greeting visitors to our new home and trying to maintain our domestic lives in the restrictive space of the museum. While we were there we performed ourselves as artists, installing and making new works/events/documentation in response to the site, and engaging in discussion about the project and implications of the work.The work 'Mr & Mrs Walker have moved' comprised our living in the site for a week. Domestic activities were carried out in the public view, either seen directly by visitors to the House, or from the street through closed circuit surveillance directed at the bedrooms, the eating area and the playpen, shown on a monitor in the window of the gallery space. Our overnight stay could be watched throughout the night.Works created during the period of Mr & Mrs Walker have moved included a sound work exploring the interconnecting space between Jim's and Helen's bedrooms; a time-based work involving the redecoration of Helen Ede's bathroom using an artist's palette and brushes; I Should Like To Live For Ever, a performance work examining the desire for self-validation through attempting to donate objects to closed collections.

Lies and Belonging (2001)

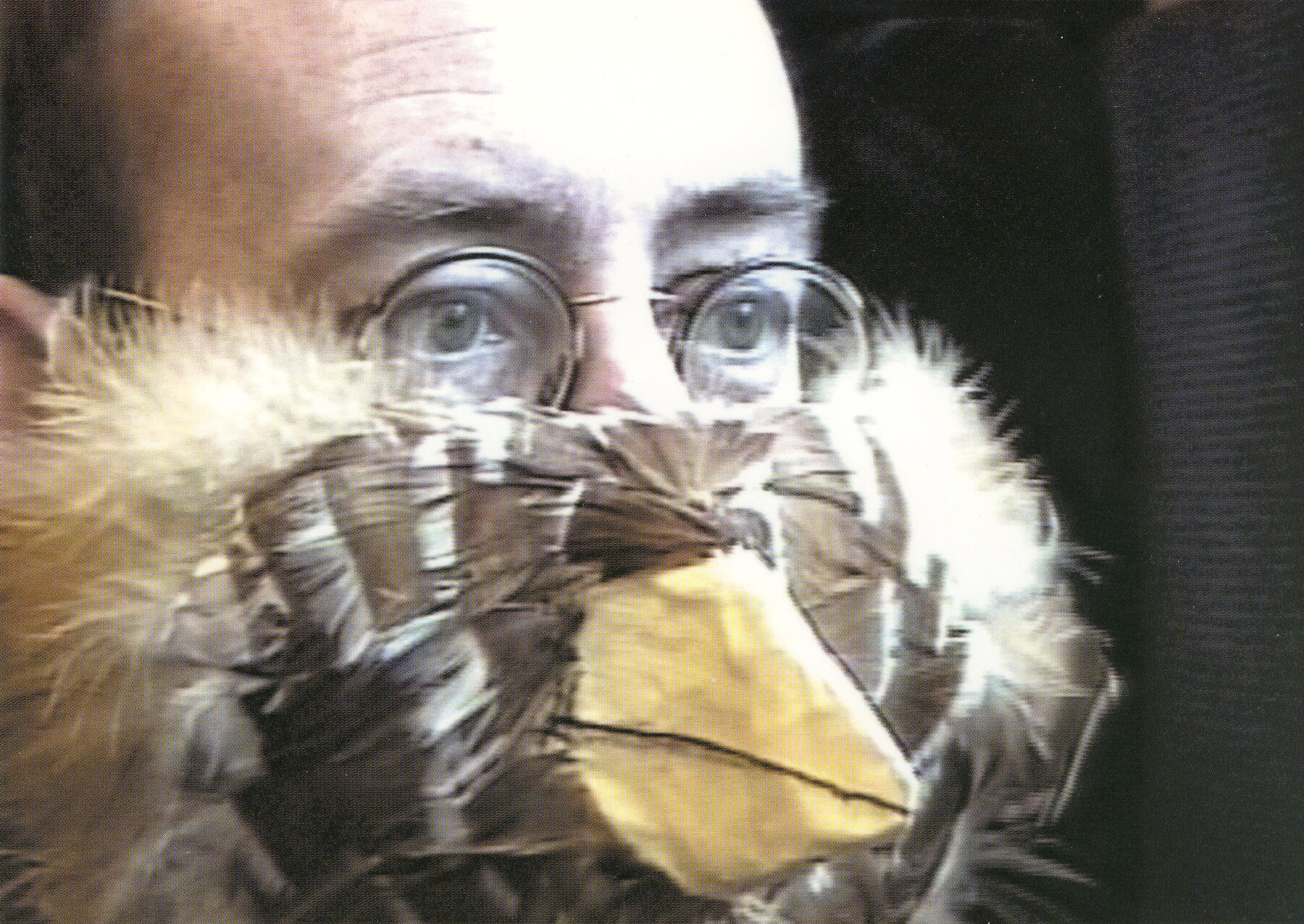

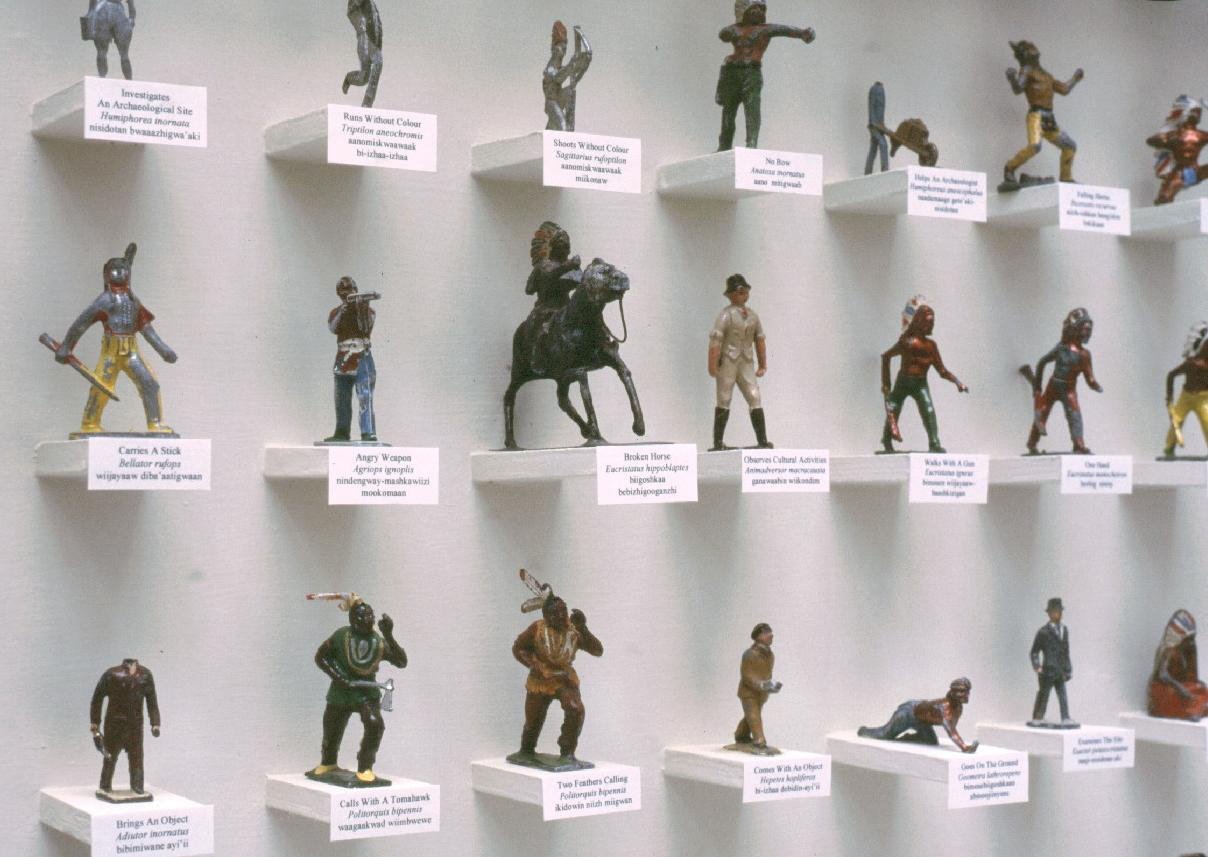

Hastings Museum & Art GalleryThis exhibition developed my fascination with the power of objects and the notions of reality, authenticity and truth attaching to them. Working with the three histories of Grey Owl, Piltdown Man, and the Hastings Rarities, the works knit a tissue of lies, denunciations, corroborations, probabilities and possibilities, in which constructed objects and the language in which they are presented create a new, and at times uncanny, reality. Focussing on particular aspects of the stories, such as hierarchies of cultures, the need to belong, and the role of text in falsehood and denunciation, the works move, like the protagonists of the histories, along apparently reasonable lines of argument to arrive at conclusions which are simultaneously desirable and uncomfortable.Archie Belaney, born in 1888 in Hastings, was brought up by two aunts and emigrated to Canada, drawn by his fixation with Native American culture. Some time in the 1920s he changed from being a fur-trapper on the fringes of Indian culture, to being a beaver conservationist and writer of articles on wilderness ecology. Encouraged and eager to move to within Indian culture to promote his local lecture series to rich holidaying whites, and already being a good speaker of Ojibwe, he re-invented himself as WaShaQuonAsin, He Who Walks By Night, or Grey Owl, at first the product of Apache/Scot parents, and finally as a full blooded Ojibwe chief. His lecture tours took him to the UK, where he spoke on radio, in lecture halls and cinemas, before royalty, and ultimately led him to Hastings, where he was recognised. The accusations of fraud, together with alcoholism, led to his death in 1938. He wrote a number of books, which are precursors of popular scientific ecology writing, and made a few short films about his life with beavers; he is currently regarded as an important founder of conservation in Canadian Parks, but probably more as an interesting identity-shifter/imposter.Piltdown Man, excavated near Uckfield in Sussex between 1911 and 1915, was unmasked as a forgery in 1953 as a result of the early use of flourine dating. The components of the skull were found to be parts of a C14 woman, and the stained canine tooth of an orang utan. The chief protagonists were Arthur Smith Woodward of the Natural History Museum, who wrote a book about the discovery entitled The Earliest Englishman (sic); Sir Arthur Keith, anatomist at the Royal College of Surgeons; and Charles Dawson, a local solicitor and antiquarian who is credited with a number of honest discoveries, and a number of hoaxes, many of which were donated to help found the Hastings Museum. All have been accused of initiating the forgery, and all are now looked on with disdain.The Hastings Rarities were a group of birds shot in the Hastings area between 1892 and 1930, mostly stuffed by local taxidermist, George Bristow, some of which found their way into Hastings Museum. Following re-examination of their documentation in 1962, a large number were declared to be fraudulent visitors and were unceremoniously removed from the List of British Birds. Some of the specimens at Hastings were found to have museum-bug and were burnt. One theory is that the alleged perpetrators, never named, were thought to have had the birds shot in Eastern Europe and shipped on ice in order to be sold at vast profit to local collectors; the recorded prices, and common sense (some of this was supposed to have happened in wartime) do not quite bear this out.The works comprise a video performance based on the desire to belong, in which the artist travels from his home to the museum costumed successively as a American Indian (the term preferred by an Ojibwe consultant), a bird and Piltdown Man; a vast collection of objects which turn Piltdown into a site of continuous and important archaeological habitation, and a number of hybrid objects creating pockets of truth within a framework of lies. These last include a neolithic taxidermy kit, an American Indian headdress made of text and bones, and a case of lead-toy archaeologists and American Indians zoologically named and labelled in English, Latin and Ojibwe.

Lie of the Land, 2006-2008

From 2006 to 2008 I worked on Lie of the Land, a Creative Partnerships project at Briscoe Nusery, Infant and Primary School in Basildon. I ran a number of activities here including a historical and museological project for the whole school, a mapping project with selected children, and a birdwatching project with nursery, Yr 1 & Yr 2, a history project with Yr 6, and a land art project with the entire school.The first project involved planting historical artefacts in the school field where the children excavated them using metal detectors; the objects were then curated and identified by the children, who then used them as the core collection around which they are creating a museum in the school; over time I introduced them to ways of researching to modify and sharpen some identifications, but the children were never “corrected” in their interpretations. We further developed the activities into story-telling, drama, and pottery-making using clay from under the school-field.See http://www.show.me.uk/site/show/STO1068.html24hourmuseum website also ran a case-study on this activity. The children developed their own research-skills as well as taking control of the design of the museum, and arranging the collections according to their own system.We developed the museum project outside the school by running it at a local open farm with another school, allowing peer-learning. CP commissioned a paper on the trade-off between KS1-2 engagement patterns and archaeological orthodoxy.The mapping project used the idea of an eighteenth–century estate map to use children’s drawings in a map of the school, which is being extended by the children into the surrounding community.We also worked with staff and children to think about ways of protecting the school from vandals. Following a successful INSET day for staff at the Horniman Museum, we used Sepik River Masks and Native American war-bonnets as a model for creating power-objects to be used around the school to explore feelings of protecting "our" space. Year 6 curriculum work on World War Two was developed into the creation of an Anderson Shelter in a classroom, which the children took over as a "safe space" to explore their own traumas and fears, resulting in the children being more able to manage their own behaviour in class.As a Creative Partnerships project, these activities were continuously monitored and evaluated. The project was favourably reported in the 2008 Ofsted report on the school.I don't think I can show a picture here without getting into trouble - because they've all got real children doing stuff. Bugger, I have good ones.

And

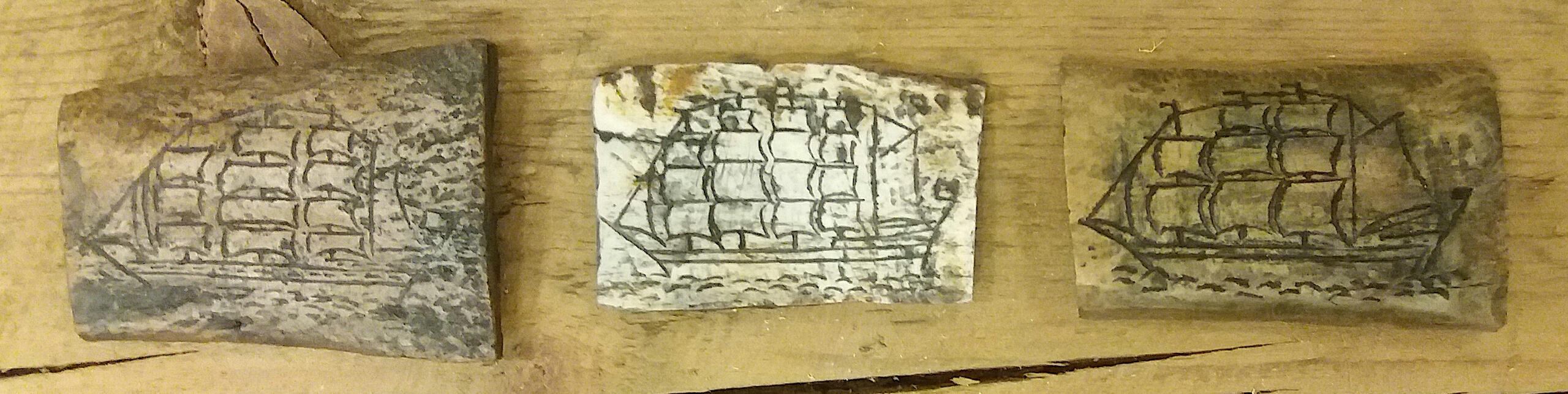

Is it ok to make things which might be mistaken for authentic objects? Are they fakes if you don't sell them as fakes? If you don't say that they are 'based on', or 'homages', or 'replicas'? Is it ok if they are just what they are, things I made after seeing - and wanting - things in museums? Just to make real the idea?

Well

More soon